Why you need a model before you try to change

Most of us don’t lack willpower; we lack a map. A good behavior model helps you diagnose the real bottleneck (motivation, skills, context, beliefs, habits) and turn intention into repeatable action. This guide curates ten trustworthy, individual-level models, each with a one-line intro, an overview, when to use it, strengths, limitations, how to start, and a 60-second example. Use it like a field manual for your own growth.

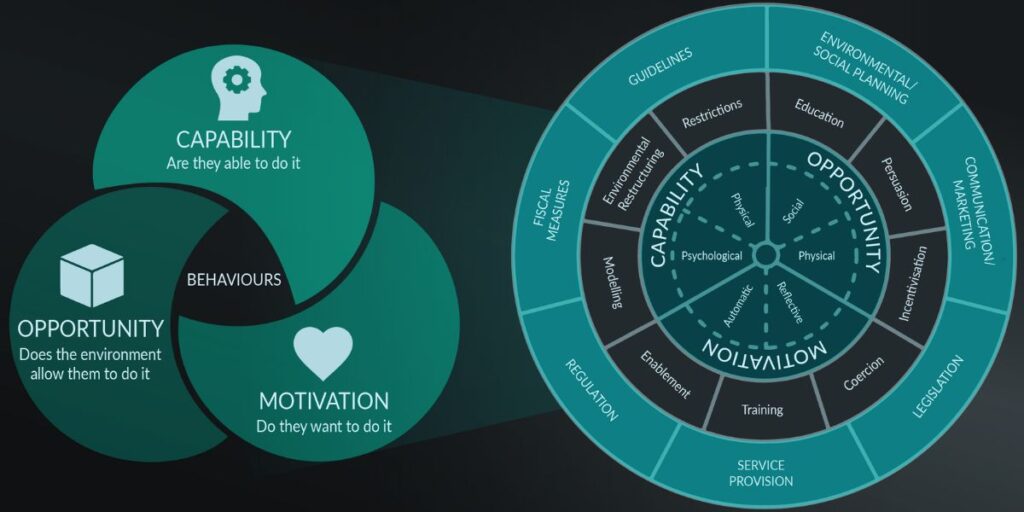

1. COM-B & the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW)

If you want to know whether you’re stuck on ability, opportunity, or motivation, start here.

Overview

Behavior (B) appears only when you have enough Capability, sufficient Opportunity, and adequate Motivation. The Behaviour Change Wheel connects that diagnosis to families of interventions and policies so you can translate insight into action.

When to use it

When you need a systems view and a clear answer to the core question: am I lacking capability, opportunity, or motivation?

Strengths

- Clear, comprehensive diagnosis.

- A practical bridge from diagnosis to intervention menus.

Limitations

- You’ll still need concrete techniques to implement day-to-day.

How to start

- Define a specific, measurable, controllable target behavior.

- Rate C–O–M on a 1–5 scale.

- Pick 1–2 matching levers: micro-skills training (Capability), default/environment setup (Opportunity), values and feedback loops (Motivation).

60-second example

“Run 3 times/week” keeps failing. Missing Opportunity (no slot, no shoes) and Motivation (low morning energy). Fix: buy shoes, lock Mon-Wed-Fri at 6:30 a.m., lay out gear by the door, auto-play your favorite running playlist when you open the door.

2. Fogg Behavior Model (B = MAP)

When a behavior just won’t “turn on” in the moment, this model flips the switch with three minimal levers.

Overview

A behavior happens only when Motivation, Ability, and a Prompt converge at the same time. If any one is missing, the behavior doesn’t occur.

When to use it

When you know what to do but can’t get started, or you’re designing reminders, checklists, or micro-flows.

Strengths

- Laser-focused on the moment of action.

- Prioritizes reducing friction over waiting for motivation.

Limitations

- Doesn’t give you a long-term roadmap; pair it with goals or habit theory.

How to start

- Shrink the behavior to a 30–120 second version to raise Ability.

- Attach the Prompt to a stable context (e.g., “after I brew coffee, I open the book”).

- Remove friction first; boost motivation later.

60-second example

Read nightly: put the book on your pillow, set a 9:30 p.m. alarm labeled “open book,” commit to one page. Crossing the activation threshold is the win.

3. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

When the real knot is beliefs, social norms, or your sense of control, this framework targets the cause.

Overview

Behavioral intention is shaped by your attitude toward the behavior, the subjective norm around you, and perceived behavioral control. Stronger intention predicts higher likelihood of action.

When to use it

When you need to recalibrate beliefs, counter unhelpful norms, or increase perceived control.

Strengths

- Pinpoints belief-level barriers and social influence.

Limitations

- There’s still an intention-action gap unless you plan the “when/where/how.”

How to start

List three supportive beliefs and three blocking beliefs. Run a tiny 7-day experiment to collect new evidence, then write if–then plans that bind intention to context.

60-second example

You believe “morning workouts drain me.” Test 10 minutes of post-dinner walking for a week and record mood/energy before and after. New data, new attitude.

4. Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

If you burn out quickly or depend on carrots and sticks, SDT explains why intrinsic motivation beats extrinsic.

Overview

Sustainable motivation emerges when your environment supports Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness.

When to use it

When you want long-horizon change that fits your life, not just a short-term push.

Strengths

- Builds durable, self-propelling motivation.

- Excellent for “designing your life.”

Limitations

- Progress can be slow if your context allows little choice.

How to start

Give yourself meaningful choices, create a just-right progression to feel competence, and join a supportive peer group to boost relatedness.

60-second example

Learning English: choose topics you love, study for 15 minutes, write one sentence you learned, and share it with a study buddy.

5. Social Cognitive Theory & Self-Efficacy

When confidence to execute is the real issue, self-efficacy belongs at the center.

Overview

Self-efficacy – “I can do this specific thing” – predicts starting, persisting, and recovering after setbacks. It grows through mastery experiences, modeling, social persuasion, and regulating emotions.

When to use it

When you hesitate to start or quit early because you think you’re not capable enough.

Strengths

- Easy to translate into micro-skills training and tight feedback cycles.

Limitations

- Requires real practice opportunities; reading alone won’t cut it.

How to start

Pick a tiny task for a quick win, find a relatable role model, ask for specific feedback, and down-regulate anxiety before the attempt.

60-second example

Fear of public speaking: record a 60-second talk to your phone, watch once, fix one thing, record again. Repeat until the improvement curve is obvious.

6. Transtheoretical Model (TTM, Stages of Change)

If you need to know where you are in the journey, TTM helps you match the right move to the right stage.

Overview

Change cycles through precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance, and sometimes lapse. Real life is cyclical, not linear.

When to use it

When you want to avoid wasted effort by aligning interventions to your current stage.

Strengths

- Prevents “stage skipping” and frustration.

- Offers stage-appropriate tactics.

Limitations

- Stages are broad; you still need concrete techniques.

How to start

Self-identify your stage. In contemplation, run micro-tests to generate evidence. In preparation, lock the calendar and write specific plans.

60-second example

Contemplating cutting sugar: try seven soda-free days and log sleep and afternoon energy. Data fuels the next stage.

7. Health Action Process Approach (HAPA)

If intention is clear but action keeps breaking, HAPA is the bridge from “want to” to “do.”

Overview

Change has a motivational phase (forming intention) and a volitional phase (planning, acting, maintaining). Self-efficacy matters in both. Two workhorse tools are the Action Plan and the Coping Plan.

When to use it

When you start and stop, or the plan falls apart after a few days.

Strengths

- Closes the intention-action gap with concrete planning.

Limitations

- Commonly used in health contexts; still requires self-management.

How to start

Write an Action Plan (when/where/what/how long) and a Coping Plan (if barrier X, then fallback Y). Put both in your calendar with alerts.

60-second example

Run at 6:30 a.m. in the park for 20 minutes; if it rains, do three plank sets in the living room after work.

8. Health Belief Model (HBM)

If you hesitate on preventive actions – screenings, exercise, vaccinations – HBM gives you the classic question set to unlock momentum.

Overview

Before adopting a health behavior, people weigh susceptibility, severity, benefits, barriers, cues to action, and self-efficacy.

When to use it

When you need to systematically dismantle hesitation on health behaviors.

Strengths

- A sharp checklist for cognitive barriers to prevention.

Limitations

- Says little about habit and environment; pair with Fogg or habit design.

How to start

Map all six elements for your target behavior. Remove any barrier you can change today: closer gym, earlier appointment slots, calendar holds.

60-second example

Write “If my doctor recommends it, I’ll schedule a Saturday morning screening,” then open your calendar and book it.

9. Habit Formation & Contextual Cues

When your goal is to “do it without thinking,” habit theory explains automaticity through context cues.

Overview

Habits form as you repeat a behavior next to a stable cue. In field studies, the median time to reach automaticity is about 66 days, but it varies widely by person and task difficulty.

When to use it

When you want consistency and reduced reliance on willpower.

Strengths

- Builds automaticity and saves mental energy.

Limitations

- Early weeks can feel slow; habits rely on a consistent context.

How to start

Anchor the behavior to a daily cue (“after lunch, walk 10 minutes”), start tiny, protect your streak, and avoid long breaks.

60-second example

Tape a sticky note that says “After lunch, walk.” Set a 10-minute timer and stand up the moment you finish eating.

10. Goal-Setting Theory

When you need a clear target and visible progress, this model turns vagueness into managed execution.

Overview

Specific, challenging goals with feedback outperform “do your best.” Mechanisms include sharper attention, more effort, longer persistence, and better strategy search.

When to use it

When you want focus, measurement, and regular review cycles.

Strengths

- Creates clarity, measurability, and cadence.

Limitations

- Over-hard goals backfire if capability is low. Pair with SCT to build skill and Fogg to reduce friction.

How to start

Translate “work out more” into “8,000 steps, five days per week, for four weeks.” Automate tracking, set a Sunday 15-minute review, and adjust by 10% as needed.

60-second example

Add the goal to your calendar, turn on step tracking, and schedule a “weekly review” reminder for Sunday evening.

Quick picker: choose by your bottleneck

- Can’t get started each day

Use Fogg to lower the threshold and add a well-timed prompt, then lock it in with habit cues. - Strong intention, weak follow-through

Use HAPA to write an Action Plan and Coping Plan, plus minimal tracking. - Beliefs or social norms are in the way

Use TPB to reframe beliefs and run micro-experiments to gather counter-evidence. - You get bored or quit early

Use SDT to raise autonomy, competence, and relatedness, and SCT to build self-efficacy through quick wins. - Preventive health behaviors

Use HBM to remove cognitive barriers, and Fogg to add prompts and reduce friction. - You need a clear target and weekly progress

Use Goal-Setting with a fixed review cadence. - Not sure what’s wrong

Run a quick COM-B scan to find the biggest gap, then pick the matching model.

A 7-step, 4-week self-design plan

- Pick the right behavior

Make it specific, measurable, and controllable. “Meditate 5 minutes every morning” beats “be less stressed.” - Diagnose with COM-B

Are you missing capability, opportunity, or motivation? Choose one primary model that fits the gap. - Lock a goal with Goal-Setting

Set a specific, challenging, but realistic target with a metric. - Wire the moment with Fogg

Shrink the first step to 30–120 seconds, attach a prompt to a stable context, and remove friction. - Write HAPA plans

Draft both your Action Plan (when/where/what/how long) and Coping Plan (if barrier X, then fallback Y). - Install habit cues

Tie the behavior to a daily anchor and protect your streak. - Run a weekly feedback loop

Every Sunday, review data, learn, adjust by 10%. Treat slips as information, not identity. If you lapse, apply relapse-prevention thinking: identify the high-risk situation, rehearse the next-time response, and restart.

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

- Aspirational goals that ignore current capability

Build micro-skills and quick wins first (SCT), then raise difficulty. - Vague timing and location

Without a “when/where,” prompts don’t trigger. Use HAPA to script the specifics. - Waiting for motivation

The Fogg lesson: remove friction and add prompts; motivation often follows action. - Believing the “21-day” myth

Habit studies show a wide range, with a median around 66 days. If you’re not automatic in three weeks, you’re normal; keep going.

The bottom line for busy people

There is no silver bullet. There is a fit-for-you model. Start with COM-B to locate the gap, wire the moment with Fogg, bridge intention with HAPA, grow staying power with SCT and SDT, set Goal-Setting targets, and stabilize with habit cues. Think small, measure honestly, adjust weekly. One clear behavior is enough to begin; the right model plus two or three techniques will carry you the rest of the way.

References

- Susan Michie, Maartje M. van Stralen, Robert West – The Behaviour Change Wheel (2011)

- BJ Fogg – Behavior Model (Stanford; behaviormodel.org)

- Icek Ajzen – The Theory of Planned Behavior (1991)

- Edward L. Deci & Richard M. Ryan – Self-Determination Theory (selfdeterminationtheory.org)

- Albert Bandura – Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change (1977)

- James O. Prochaska & Carlo C. DiClemente – Transtheoretical Model

- Ralf Schwarzer – Health Action Process Approach

- Irwin M. Rosenstock – Health Belief Model

- Phillippa Lally et al. – How are habits formed? (European Journal of Social Psychology, 2009)

- Edwin A. Locke & Gary P. Latham – Goal-Setting Theory (American Psychologist, 2002)